This exhibition brings together several overlapping themes relating to the “position” or place of painting today. It takes its basic form from an important debate, now some eighty years old, involving the so-called Frankfurt School and its correspondents, Ernst Bloch, Bertolt Brecht, Georg Lukács, Walter Benjamin, and Theodor Adorno. Brecht and Lukács took realism to be art’s most powerful critical response to the commodification of culture under Capitalism, while Adorno vociferously countered that it was only by abandoning representation per se that art could prevent its own imminent reduction to triviality and farce. For this uncompromising critic of society and culture, abstract art’s refusal to wave the banner of the Left, or indeed of any other party or stance, comprised its greatest strength. “If any social function can be ascribed to art at all,” Adorno noted, “it is the function to have no function.”

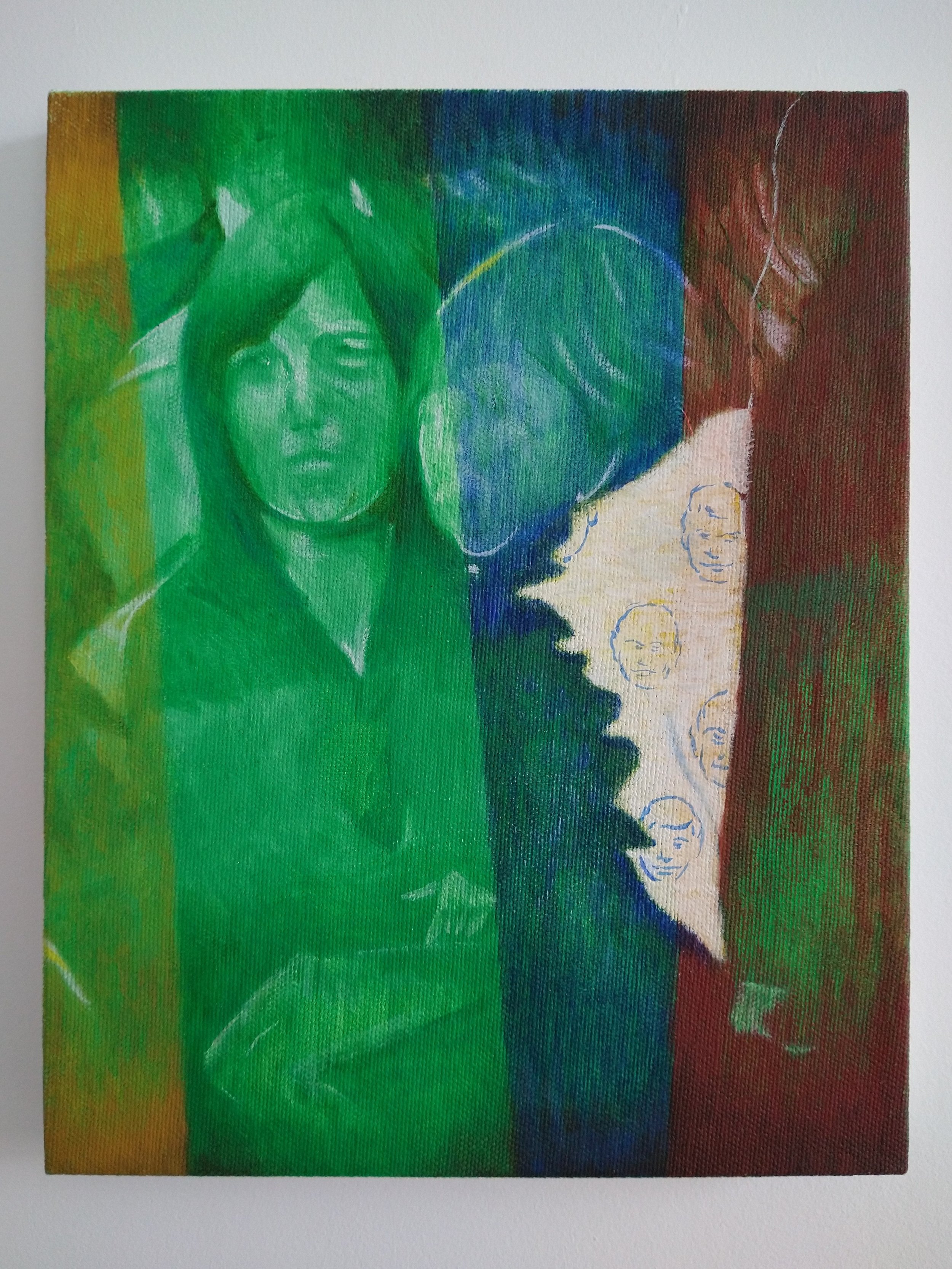

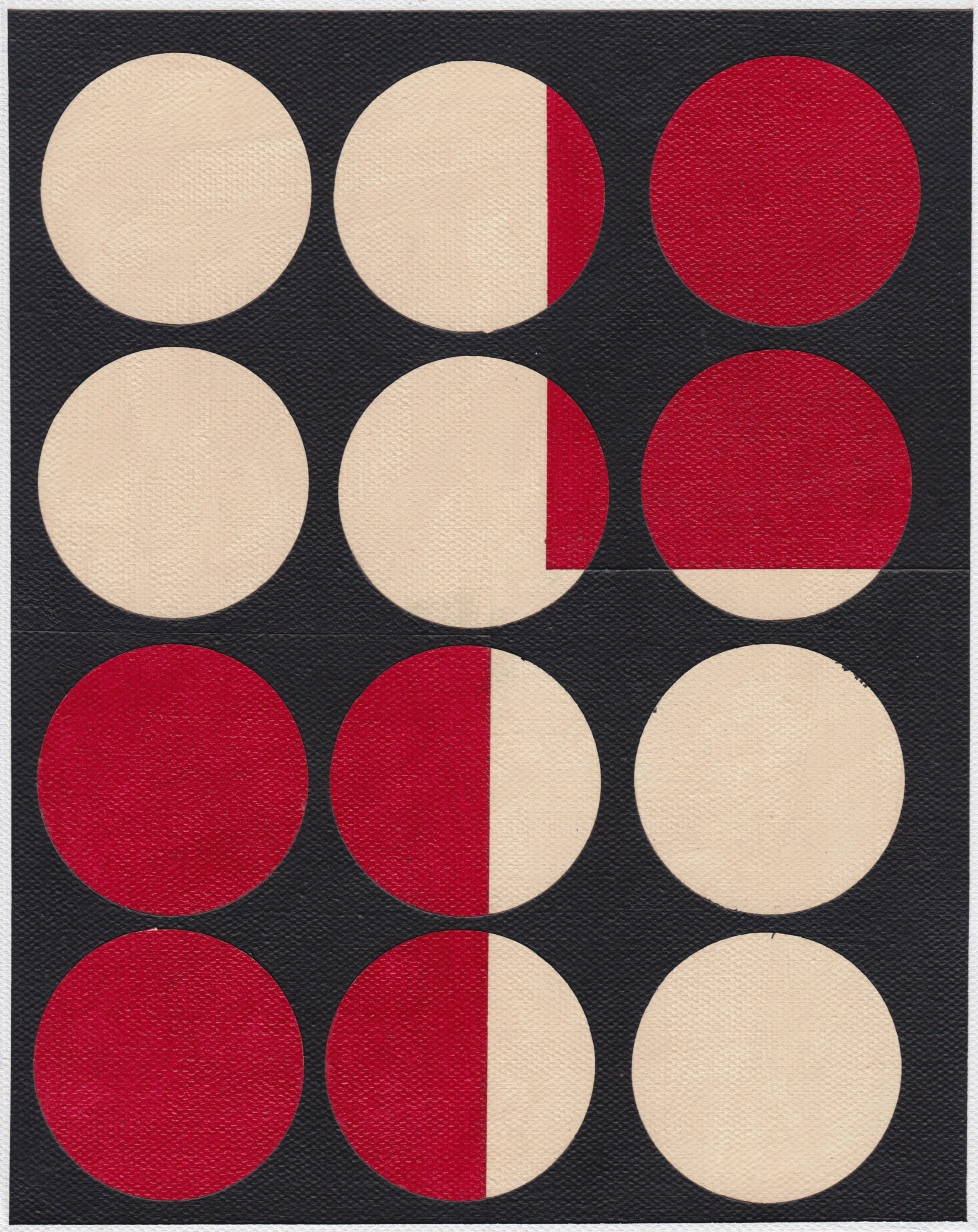

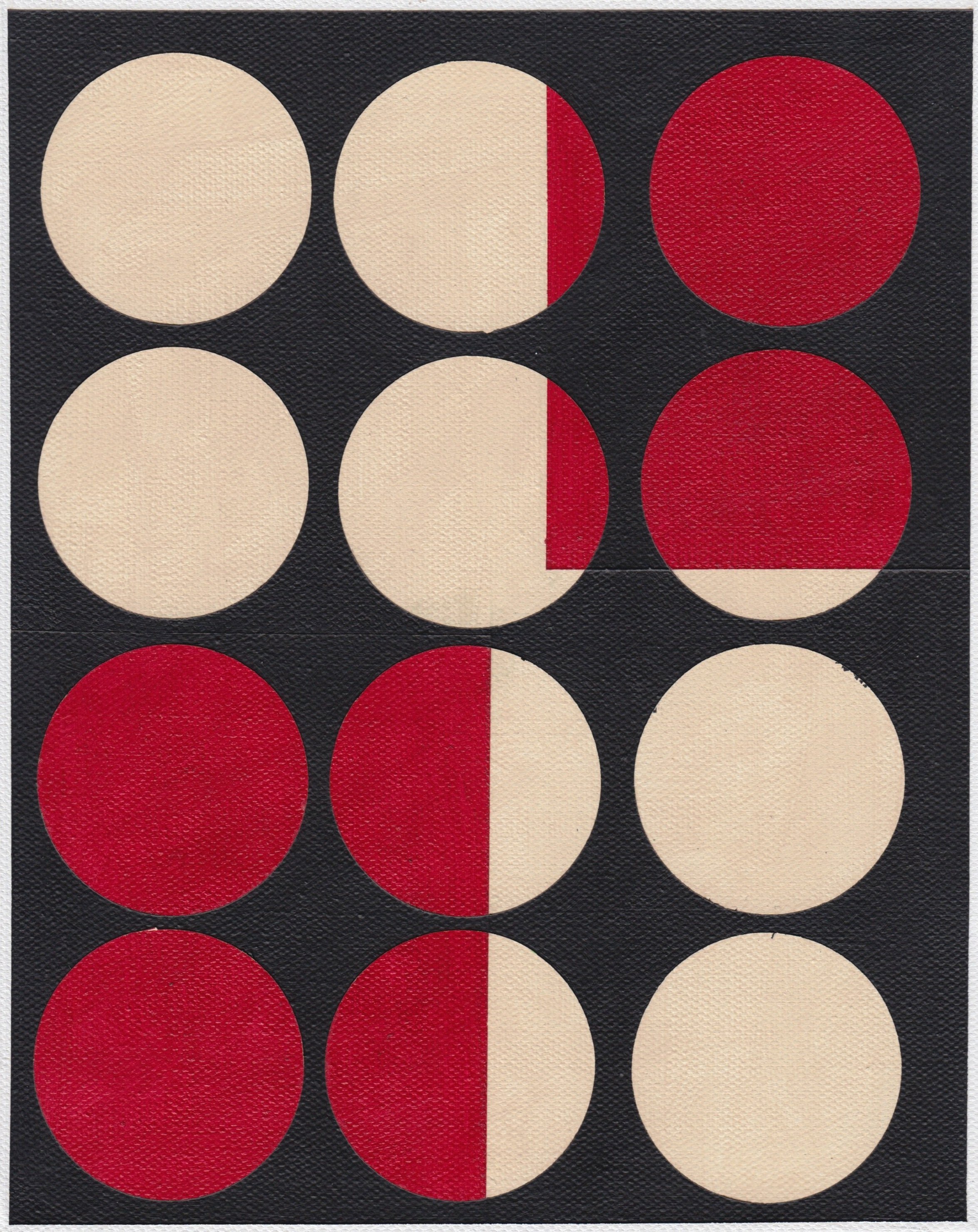

In the present display, works by two explicitly figurative painters, Louise Bristow and Derek Hampson, have been juxtaposed with abstract paintings by Peter Suchin and Chris Tosic, setting up what is effectively a spectrum or sliding-scale of painterly modes. Simon Patterson, whose practice has employed painting as well as many other visual/textual forms, has been invited to respond to this arrangement. His contribution may emphasise painting as an ancient and continuing practice or, conversely, cast doubt on the medium’s supposed certainties, opening up possibilities which direct the viewer’s attention towards entirely other areas of interest or concern.

The initial motivation for this show emerged from private discussions around the “validity” of abstract art today, when painting’s new-found popularity is paradoxically compromised by an expanded but incestuous art market, and through social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram. Supported by these now naturalised manners of transmission, “painting” is more widely disseminated than ever before, but at the cost of its sensuous materiality and experiential address. Has abstraction, once regarded as a critical, dissenting force, become mere decoration, a light aesthetic thrill, with figuration assuming the present mantle of seriousness and critique? Or, more extremely, can it be that the general category of painting has simply been rendered immaterial by conceptual, digital, and corporate channels of exchange? Prioritising specific artistic mediums may appear irrelevant under present conditions of culture, but artistic autonomy remains an indispensable feature of any artistic practice worthy of the name. As the Art & Language group – another central reference point for the present show – rightly insist, the only way to prevent artworks being co-opted by external interests is by maintaining “a certain internality” of structure or form, aesthetically sealing off the work from intrusion by unwanted ideologies. Despite their importance, in the 1960s and ’70s, as Conceptual Art pioneers, A&L have increasingly defended the critical potential of painting in preference to the too-readily institutionalised practices of their fellow Conceptualists. A&L consciously echo Adorno’s remarks on how works of art are “hermetically closed off and blind, yet able in their isolation to represent the outside world”. Such claims may be applied, in a positive fashion, to both the figurative and non-figurative works in Painting in a Painting of Itself.

It was Adorno too who recognised that “The only relation to art that can be sanctioned in a reality that stands under the constant threat of catastrophe is one that treats works of art with the same deadly seriousness that characterizes the world today”.

References in order of citation: Ernst Bloch, Georg Lukacs, Bertolt Brecht, Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno, Aesthetics and Politics, NLB, 1977; Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, RKP, 1984, p. 322; Art & Language, “Feeling Good: The Aesthetics of Corporate Art”, in Armen Avanessian & Luke Skrebowski (Eds.), Aesthetics and Contemporary Art, Sternberg Press, 2011, p. 173. (See also Paul Wood, “Refusing to Die”, Art-Language, New Series Number 2, June 1997); Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, RKP, 1984, p. 257; Adorno, Prisms, MIT, 1981, p. 185.